A questionnaire was sent to British rescues not on the Greyhound Board of Great Britain (GBGB) Homing Scheme. Criteria included that the greyhounds had to have raced on British tracks.

The GBGB’s Greyhound Homing Scheme – when greyhounds are registered to race with the GBGB, the trainer gives a £200 bond to the GBGB. When the greyhound has finished racing, the £200 trainer’s bond plus £200 from the GBGB, £400 in total is given to the homing organisation, as long as it is on the approved list. Rescues and organisations that highlight the reality of greyhound racing are not allowed to be part of the scheme.

Some rescues did not complete the questionnaire due to being too busy (as there is a homing crisis); one rescue stated concerns that they would be harassed by participants and supporters of greyhound racing even though the results would be anonymous.

RESULTS

The results are over two years, 2022 and 2023, and a total of 410 greyhounds.

The ages ranged from 1 – 12 years with the average being 4 years old. Male:Female ratio was 55%:45% (226:184)

Rescues had around 30 greyhounds on each of their waiting list, with an average wait time for rescue space of 3 months. The average time they stayed in rescue was 11 weeks.

Of the 410 greyhounds, 11% (45) had been at risk of being killed.

78% (320) of the greyhounds came from trainers that were on the GBGB homing scheme. Not all of the trainers gave their £200 bond from the scheme to the rescues, one rescue said 75% of their trainer did. The time the trainers had waited for a space on the GBGB scheme ranged from 3 months to a year.

The condition of greyhounds coming into rescue varied, rescues saying it depended on the trainer.

Costs

The cost of homing a greyhound without any extra expenses for injuries etc was an average of £1,625 (ranged from £1,200 – £2,000).

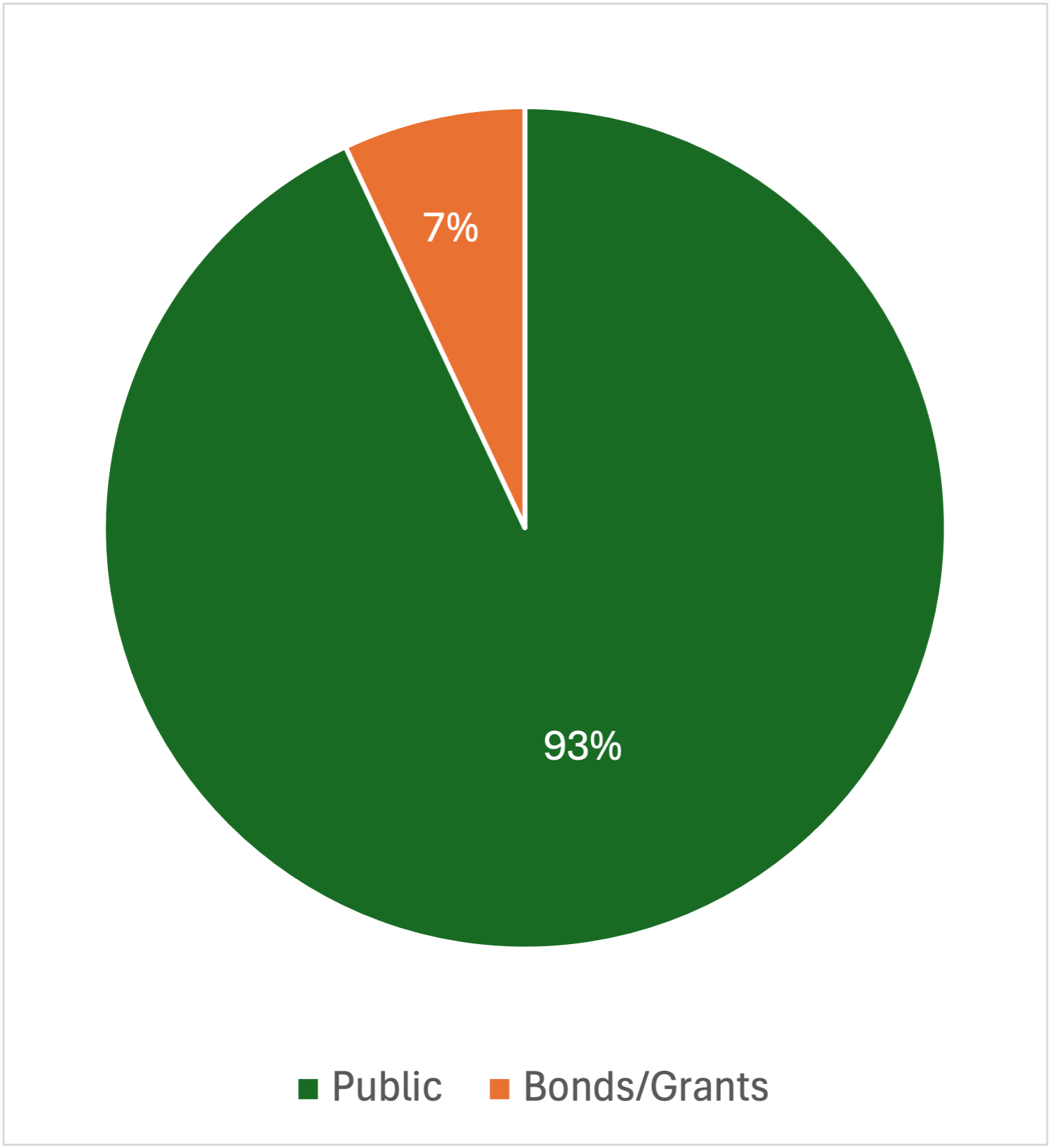

Most of this was funded by the public, an average of 93% equating to £1,511 per greyhound.

Injuries

Results here are incomplete as one rescue could not give the exact number of greyhounds injured, so the figures given are lower than the true number.

16% (66) of the greyhounds arrived with injuries, 5% (3) of those injured had major injuries that were not treated.

At least 9% (38) of greyhounds had a history of a previous fracture. Rescues did state that they were not always told if there had been a previous injury. On several occasions this had lead to further fractures at the injury site as the rescue had not been aware and therefore not limited the dogs running in their field.

Minor injuries cost anywhere between £300 to £3,000 to treat while major injuries could cost as much as £8,000.

Dental Disease

50% (203) of greyhounds had minor dental disease which cost on average £500 to treat.

35% (142) had major dental problems costing between £800 to £1,500 to treat.

Comments from Rescues

Rescues approached, even those that did not complete the survey, said that the GBGB homing scheme was not working. Some rescues said they had been approached several times to join the scheme with the

GBGB representative being ‘persistent’.

Homing is ‘…getting worse, rescues on the scheme are cherry picking the greyhounds.’

‘The number of ex-racers coming out of the industry far exceed the number of rescue spaces available. The pressure on rescues to keep up with demand is ever increasing, the situation is far from improving. The Bond should be paid to the rescue/organisation caring for the dog, regardless of racing stance.’

‘The GBGB needs to have a conversation with us, we may be anti-racing but we and the other rescues who are also anti-racing, are are still a valuable resource that could help to improve the welfare of greyhounds, if we open up a dialogue.’

CONCLUSION

This survey highlights several things, but there are limitations due to incomplete data and lack of transparency from the greyhound racing industry, such as number of greyhound that are homed by independent rescue not on the homing scheme.

11% of greyhounds were saved from being killed, showing the vital work the independent rescues do.

There have been no public figures to date on the number of greyhounds leaving racing that have had fractures. In this study 10% of greyhounds that came into rescue had a fracture (current and previous), and 16% arrived with an injury; at least 25% of greyhounds leaving racing had suffered an injury.

The study, in line with previous reports, shows a high incidence of dental disease in racing greyhounds, 85%.

Over 90% of homing costs are covered by the general public, for these 410 greyhounds, a fraction of those homed independently, the public donated at least £620,000, which the rescues had to source. According to the Retired Greyhound Trust their average homing cost per greyhound in 2023 was £1,625, with their £400 bond per greyhound from the scheme, that still left them with 75% of the homing cost to raise, over £1.5 million.

Greyhound racing is part of the multi billion pound gambling industry, yet it relies on the public to fund millions of pounds every year to home their greyhounds.

Rescues confirm that certain trainers are known to keep greyhounds in poor condition, which raises concerns on the GBGB and track vets actions or lack of.

Why does the GBGB data not have a category for greyhounds homed by rescues outside of the scheme? Is it because it would highlight how much the industry homing schemes are failing?

In essence the GBGB thought that they could stop greyhounds going to rescues that were anti racing, without any consideration of the greyhound welfare issues this would cause. The scheme does not have enough organisations to home the greyhounds being discarded by the racing industry every year and is contributing to the greyhound homing crisis.

The GBGB homing scheme is failing the greyhounds, with hundreds of greyhounds stuck in trainers kennels 1,499 greyhounds staying with trainers in 2023 compared to 715 in 2022, and an increase in the number of greyhounds being killed due to homing issues – 55 greyhounds in 2023 compared to 20 in 2022

(GBGB-VERIFIED-Injury-Retirement-Summary-2023.pdf).

Quote from another independent rescuer:

‘Their scheme comes with silencing that most of us will not buy into. With no list, no support and no spaces the greyhounds are now piling up in trainers kennels. We are seeing what we expected to see…. unneutered greyhounds turning back up in the stray pounds…Once again my question to the GBGB…. when will you release the absolute FULL TRUTH of numbers. They are once again falling through cracks.

You are not fit for purpose, you never have been.’

With special thanks to Forever Hounds Trust and to the rescues that took part for their assistance with this study.